Carried interest is a partnership tax concept, a hallmark of investment fund economics, and a driver of powerful estate planning opportunities. At the same time, complex tax rules pose traps for the unwary. This article introduces the most common technique to navigate estate planning with carried interest: the “vertical slice.”

The federal income tax treatment of carried interest is beyond the scope of this article. For federal estate and gift tax planning with carried interest, the key legal issue is valuation. Generally, a well-planned inter-generational transfer involves an asset with little value at the time of transfer and which, post-transfer, appreciates greatly in value. The low value at transfer—not the high value post-transfer—applies against the transferor’s lifetime federal estate and gift tax exemption amount (which amount is a moving target politically and $13.61 million in 2024). On its face, carried interest appears ideal for estate and gift tax planning because it has arguably zero value when created, yet it may appreciate greatly.

Internal Revenue Code Section 2701 complicates the analysis. At a high level, Section 2701 applies an unfavorable valuation rule where a transferor (i) transfers a subordinate equity interest in a privately held entity to a family member, and (ii) retains a preferred equity interest in the same entity. One way a retained equity interest may be considered “preferred” is through preferential distribution rights, which are typical in the distribution waterfall of a private investment fund.

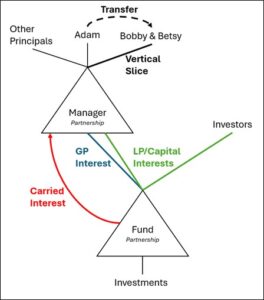

An example illustrates the application of Section 2701 to carried interest. Imagine two entities which are partnerships for tax purposes. The first partnership is an investment fund, and the second is the manager of the fund. Outside investors contribute capital to the fund in exchange for substantially all “capital” or “limited partner” interests, which confer economic ownership of the fund. The manager contributes a small amount of capital to the fund for a sliver of the capital interests. The manager also holds complete managerial control of the fund through “general partner” interests. The basic economic arrangement is that the manager deploys the capital of the outside investors through the fund. In exchange, the manager receives a management fee (e.g., 2% of fund assets under management, regardless of performance) and carried interest (e.g., 20% allocation of fund income exceeding a pre-determined “hurdle” rate). That carried interest has tremendous upside potential.

Now assume that Adam, a partner in the management entity, is creating his estate plan. Adam directs the manager to transfer only Adam’s share of the manager’s carried interest to his children, Bobby and Betsy, shortly after the carried interest is first created and has minimal value. Adam’s intention is that several years following the transfer, assuming the fund performs well and delivers returns above the hurdle rate, the value of the carried interest Adam transferred will be high. Therefore, Adam will have used only a miniscule amount of his gift and estate tax exemption (based on the low value of the carried interest at the time of the transfer), yet ultimately transferred substantial value to Bobby and Betsy (based on post-transfer appreciation). However, because (i) the fund manager holds both a capital interest and a carried interest in the fund, and (ii) the capital interest has preferred rights to distributions (i.e., the hurdle), Adam’s transfer triggers Section 2701. Therefore, for estate and gift tax valuation purposes, Section 2701 treats Adam as if he had transferred his share of both the fund manager’s carried interest and the fund manager’s capital interest. Because the fund manager’s capital interest is funded by capital contributions, its value at the time of Adam’s transfer is likely much greater than the value of the carried interest, resulting in a much greater deemed transferred interest against Adam’s estate and gift tax exemption. Thus, the deemed result under Section 2701 inflates the value of the actual transfer, causing distorted and adverse tax consequences.

Enter the vertical slice. The vertical slice provides a safe harbor against Section 2701. Instead of transferring only his share of the carried interest, Adam transfers a “vertical slice” of all of his economic participation in the fund, including proportionate amounts of both carried interest and capital interest. Here, the simplest way to do so would be for Adam to transfer a portion of his interest in the partnership that is the fund manager. That partnership interest holds indirectly Adam’s share of both the carried interest and capital interest in the underlying investment fund. The diagram below shows a simplified vertical slice transfer.

Unlike under the application of Section 2701, Adam’s share of capital interest is actually transferred rather than only deemed transferred for valuation purposes. Thanks to the vertical slice technique, (i) Bobby and Betsy actually enjoy ownership of the capital interest, and (ii) the tax result follows the economic reality.